High freight rates and steep drops in traffic have led many commercial airlines to swap out passengers for cargo and may tempt cargo carriers to update their ageing fleets. Is this just a passing trend or a long-term market change?

Throughout the aviation industry’s prolonged COVID-19 crisis, a number of airlines have tried to make up for their steep losses in passenger revenue by transporting cargo in their bellies and cabins. As we reported in one of this month’s related articles, 200 airlines operated well over 2,500 of these so-called “preighter” flights in 2020. But some companies have gone even further by converting their parked passenger aircraft into freighters. Global aviation data firm Cirium found that between March and December 2020, 155 aircraft had all or most of their passenger seats removed in order to transport more cargo in their cabins.

With online shopping booming and an urgent global demand for vaccinations and medical supplies, it’s hardly surprising that airlines would want to make up some lost revenue by carrying cargo rather than passengers. But are passenger-to-freight (P2F) conversions long-term winners for airlines or will newly-configured aircraft be reconverted back into passenger aeroplanes as soon as travel demand returns?

Tough economic decisions

According to Cirium, the rate of conversions has already slowed down significantly. One hundred and sixteen passenger aircraft were converted to cargo in Q2 2020 while the second half of the year saw only 32 conversions. Sixty of the 155 converted passenger planes had completed their stints as “preighters” by mid-January 2021, with Cirium reporting that the majority of those had returned to passenger service.

“It seems likely that many will conclude cargo operations, have their seats reinstalled and gradually return to passenger services throughout the year,” Cirium’s senior aviation data research analyst James Mellon said.

Airlines have to consider the economics of their cargo operations, Mellon’s colleague Chris Seymour added.

“Loading cargo into cabins requires a lot of manpower, compared with loading it into aircraft bellies in containers and on pallets,” Seymour, the head of market analysis at Ascend by Cirium, said. “The issue for airlines is whether they spend money on reconfiguring cabins, or to simply operate aircraft with cargo loaded in the belly and on the seats if required.”

Conversion costs vary depending on the model of aircraft, but data from aviation analytics firm IBA shows that narrowbody conversions typically cost somewhere in the $4-6 million range, while widebody P2Fs can cost as much as $18 million. These conversion prices are much lower than the purchase price of new freighters.

The dominant aircraft in the widebody freighter segment is the Boeing 767-300, with 315 aircraft in service and another 26 conversions slated for the next 12 months. IAB estimates the average conversion price of a 767-300 at $14.7 million, while the purchase price is $220.3 million.

From parked to cargo?

Many airlines were forced to park sizable portions of their fleets during the COVID-19 crisis and plans to retire older models have been accelerated. This could make the idea of P2F conversions appealing for major cargo carriers like FedEx and DHL, but as IBA president Phil Seymour pointed out, the market dynamics are complicated.

“The clear and strong growth in [freighter aircraft] demand is not driving up values and lease rates as it normally would,” Seymour said. “While the global freighter fleet is growing as is the number of conversions, there has been a corresponding increase in aircraft available for conversion driven by the accelerated retirement of passenger aircraft fleets. This has meant that freighter values and lease rates have actually seen a modest drop.”

With freight rates currently at a record high and a glut of parked commercial aircraft, major cargo carriers could view this as an opportune time to update their ageing fleets. According to Aerotime Hub, the average fleet age for FedEx Express, UPS Airlines and DHL Aviation are all at or around 20 years, with some DHL branches using aircraft that are more than 36 years old.

Aircraft that have been parked because of the crisis are the most likely candidates for P2F conversions, particularly models that may be approaching a natural retirement age from passenger operations but may still be younger than the cargo carriers’ current fleets.

But Boeing’s director of freighter conversions, Jens Steinhagen, told Flight Global that it’s not just the older models that are getting converted. Prior to COVID, most passenger aircraft converted into freighters had been in service for 12 to 20 years old but Steinhagen said the company is now seeing some of its 737 models undergo P2F conversions before they’re even ten years old.

Steinhagen said the pandemic has created a “perfect storm” for passenger-to-cargo conversions.

“During 2020, the passenger fleet was largely parked and the industry realised this was going to be a long-term thing. This improved the availability of feedstock and helped to bring down the price of the asset,” he told Flight Global.

The Satair Takeaway

The P2F market is expected to remain strong in the short term but most industry experts think it will naturally level off at some point. The risk for operators who invest in P2F conversions is that if passenger traffic quickly bounces back to pre-crisis levels, the return of belly-hold capacity could be enough to accommodate much of the air cargo demand, which analysts predict will remain stifled as a result of the recession.

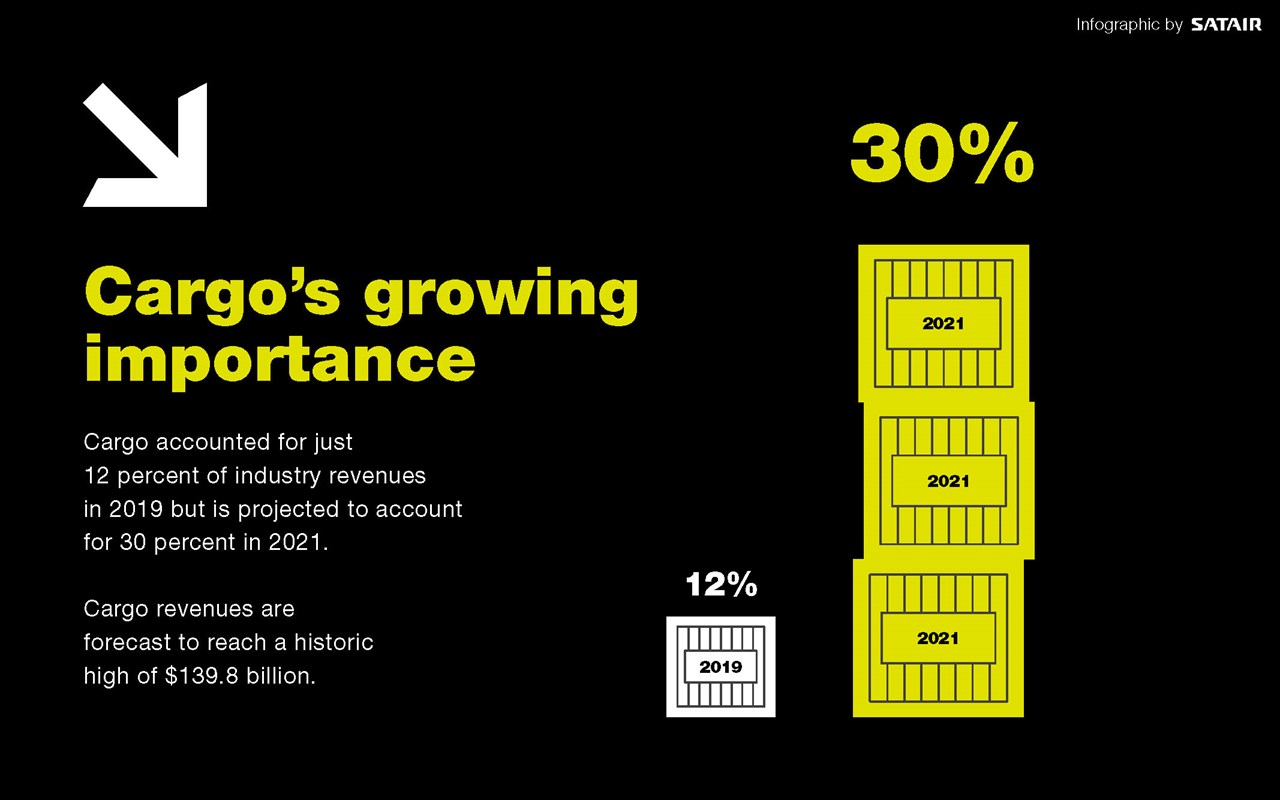

One thing the industry can almost certainly count on is that cargo flights will represent a larger slice of aviation’s overall revenue in 2021 than it did pre-pandemic. Cargo accounted for just 12 percent of industry revenues in 2019 but IATA expects that to reach 30 percent in 2021, as cargo revenues are forecast to reach a historic high of $139.8 billion.

In the long-term, global air cargo traffic is forecast to grow by four percent a year over the next two decades. In Boeing’s World Air Cargo Report from last October, the airframe manufacturer predicted that the world’s dedicated freighter fleet will grow by more than 60 percent over that time, and that nearly two-thirds of the deliveries will be conversions from passenger aircraft.