Should the airlines have been bailed out? Supporters say that without aid, bankruptcies would have cost thousands of jobs throughout the supply chain and stifled a wider economic recovery.

Eighteen months after the COVID-19 pandemic halted international travel, it feels repetitive to detail just how badly the aviation industry was hit. But a few key numbers bear repeating: revenues per passenger-kilometre fell by 66 percent. Around two-thirds of the entire global fleet was parked. And nearly 1,500 aircraft deliveries planned for 2021-2022 have either been pushed back or cancelled.

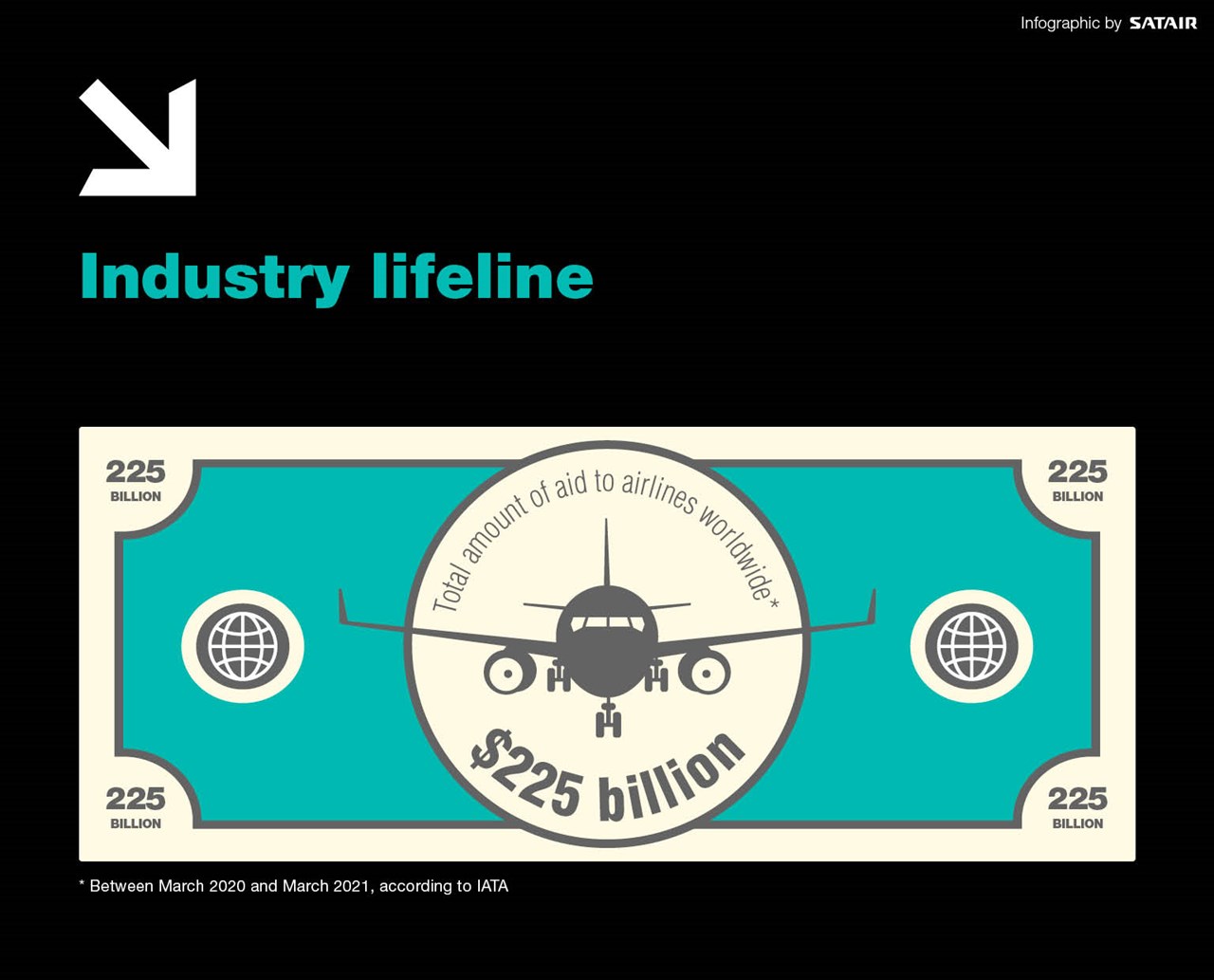

That things don’t look even worse than they do is largely due to another eye-popping number: $225 billion. According to IATA, that’s the total amount that governments worldwide gave airlines during the first twelve months of the crisis. Whether it took the form of direct aid, wage subsidies, loan guarantees or tax breaks, this government aid allowed airlines to keep operating on a limited basis throughout the crisis and quickly ramp up as soon as travel restrictions were lifted.

RELATED ARTICLE:

Should airlines have been allowed to fail?

Controversy and criticism

But the bailouts were not without controversy. As we explore in this month’s related article, critics have argued that the bailouts do little, if anything, to address the industry’s underlying problems, that they served mostly to let airline executives off the hook for their own mistakes and that governments should have tied their assistance to airlines meeting certain climate conditions.

But for industry analysts like Richard Brown, the managing director of aerospace consultancy Naveo, there’s little doubt that the bailouts were necessary.

“Supporting airlines was the right thing to do,” Brown told the Satair Knowledge Hub. “In an unprecedented situation like COVID, where people cannot travel, it is the responsibility of governments to support viable industries that were forced to shut down due to mandated restrictions. In a global, connected world, airline service is vital for economic growth.”

Bailouts over bankruptcy

The government assistance proved to be a vital lifeline for airlines. Despite 2020 being the worst year in aviation history, just 43 airlines filed for bankruptcy, fewer than in both 2018 and 2019.

A spring 2020 report from the International Transport Fund estimated that when the pandemic hit, airlines only had enough cash reserves on hand to survive two months of crisis conditions. Left to fend for themselves, many airlines would have filed for bankruptcy by May or June 2020.

“Without government support, we would have seen airline failures,” Brown said.

The public funds also helped airlines secure additional funds from private investors. Writing in his company’s 2021 Aviation Industry Leaders Report, KPMG of Ireland’s head of aviation finance, Joe O’Mara, said the bailouts “succeeded in boosting investor confidence around the world.”

“Having that government backing in place offers comfort to investors, boosting the ability of aviation companies to raise funds in the capital markets,” O’Mara wrote.

With the influx of state and private money, airlines were able to provide limited services throughout even the worst parts of the crisis and then quickly expand their offerings once travel restrictions began to loosen.

“The government support provided a bridge that allowed the employees and their skills to be retained until they could safely restart operations,” Brown said, adding that it is very unlikely that airlines could have ramped us as quickly as they did when travel demand bounced back.

RELATED ARTICLE:

Industry analyst: "Supporting airlines was the right thing to do"

Jobs saved throughout the supply chain

Brown and other advocates of the bailouts also point out that the government aid saved thousands upon thousands of industry jobs. As many as 75,000 aviation jobs were saved in the United States alone, with the majority of those workers able to collect full pay throughout the downturn.

But the saved jobs were not just at the airlines. The downstream effects of the government aid benefited workers throughout the aviation supply chain: from airport workers to manufacturing and maintenance jobs.

“As aircraft flying activity results in maintenance and overhaul requirements, it meant that the airlines that received bailouts (or gained their injections of capital via the markets) could keep some of their fleet flying and continue maintenance activity,” Brown said.

Keeping maintenance and repair work running throughout the crisis, albeit at a much lower level than normal, helped buoy a global MRO aftermarket that saw revenues decline by an estimated 50 to 60 percent in 2020 and is forecast to suffer a 25-35 percent drop in 2021.

As for the OEMs, Airbus was a direct beneficiary of France’s €15 billion in financial support to the aerospace sector. Boeing turned down a direct bailout but nonetheless was buoyed by “a backdoor bailout” that allowed it to borrow some $25 billion from investors.

While hardly a cure-all for the plane-makers – Airbus eliminated 11 percent of its global workforce while Boeing has said its global staff will shrink by around 20 percent by the end of this year – the ability of the world’s biggest OEMs to weather the storm helped most larger Tier 1 suppliers do the same. Many smaller manufacturers were not as fortunate, however. Some analysts think that upwards of 20 percent of Tier 3 suppliers may not survive, pointing to the fate of Impresa Aerospace, which filed for bankruptcy despite receiving $2 million in government aid.

The Satair Takeaway

The bailouts were no panacea. And with a full industry recovery not expected until 2024, we may not have seen the last of them. Even the most ardent industry supporters can acknowledge that some of the criticisms of the government aid packages are valid. Although we’ll never know how things would have looked if governments had not stepped in, it’s a safe assumption that the airlines, and the entire supply chain that they support, would be in much worse shape if they had not been thrown a lifeline.